by Rich Moreland, August 2016

In this post, we’ll find out about Jac Avila’s background and his view on the female characters he creates.

* * *

Jac Avila is of international stock. His father was from Holland and his mother, Bolivia, giving him a heritage that is Dutch, Spanish, Basque, and French.

Born in Bolivia, Jac grew up in a Catholic society, a culture that takes on its own identity and values which many Americans don’t grasp. We tend to compartmentalize religion, often limiting it to merely attending church, and don’t see it as a larger social/cultural ingredient in our lives.

On the other hand, a Catholic society is overarching, emphasizing spiritual issues without negating worldly values. For example, it insists that learning take center stage in a child’s life.

“I was educated in the most exclusive Jesuit school in La Paz,” Jac points out with pride. “The education was secular with a big emphasis on science. No conflict there. As a matter of fact, Jesuit priests were very much ahead in everything. The religious aspects of our education was a mixture of ethics, morals, mysticism and the understanding that a great part of the Bible is rather symbolic and mythological.”

Sadly, his mother passed away before Jac entered his teenage years. His father moved Jac and his brothers to New York City where the future actor/director/producer studied movie making, art, and photography.

The Blue Buick

“After graduation I started working at CBS and later at a photo studio specializing in advertising. I quit my job in 1979 to become an independent filmmaker. By 1982 I was making my first film in Haiti and Cuba by way of New York and Miami,” Jac explains.

The film premiered at Cannes in 1988.

“It took me that long to make it,” he confesses, not surprising under the circumstances.

Facing expenses that can easily derail projects, Jac spent most of his time doing what indie filmmakers learn is part of the game: meeting the right people and raising money.

Facing expenses that can easily derail projects, Jac spent most of his time doing what indie filmmakers learn is part of the game: meeting the right people and raising money.

The film was Krik? Krak! Tales of a Nightmare which Jac co-produced and directed with Vanyoske Gee. Jac characterizes the production as “a surreal/expressionist docu-nightmare” about the brutal regime of Haiti’s Papa Doc Duvalier that includes the spiritual aspects of Haitian culture.

The work, though difficult, answered “a more political, radical call” for him, Jac declares, and was definitely a “challenge.”

And rewarding . . . the critics received it favorably.

“Le Cahiers Du Cinema, foremost film magazine in France described it as a great horror film in the tradition of Witchcraft Through the Ages,” Jac remembers.

From there he made a television mini-series and a handful of documentaries before shooting a “‘performance'” video, an inexpensive “project that started something unexpected that built everything” he is currently doing.

Jac explains how it happened.

When he was visiting Cuba, he developed a script about a young woman during the island’s colonial days who “has fantasies about being a martyr,” a practice common in “the traditional holy week procession.”

Carmen Paintoux had the lead role in Jac’s mini-series at the time and they discussed staging the girl’s fantasy for video. “During that process, she created Camille who is the central character in Martyr,” Jac says.

The short film was born and the budding filmmaker’s career took on a new direction.

A remarkable journey for a little boy who saw his first movie at age four. Its violence left an impression. The Film? Walt Disney’s Bambi.

“I don’t remember anything before the movie. I remember everything after the movie, even the song that was playing on the radio when my uncle drove us back home in his blue Buick.

“From that moment on all I wanted in life was to know about that fantastic thing I experienced that day.“

Magic to Art

Considering what he’s told me, I ask Jac if he designs his films to be political and religious commentaries.

“Not necessarily,” he begins. “Art is beyond those limiting systems. While religion tries and fails to interpret the unknown and the mysterious, politics often try, earnestly, to fit a square into a triangle, with fatal results.”

Having said that, Jac admits his explanation may sound “a bit simplistic, since both religion and politics are mechanisms humanity uses to organize itself into something manageable.”

“In a way, mankind created gods to control itself,” he believes. But in time, more practical attitudes took shape and the overarching role of the gods receded in favor of elected leaders in civilizations like Classical Greece, for example.

Nevertheless, there is a magic to art, Jac insists.

“Art interprets what we see and turns everything on its head, art can also imagine a million futures and a million pasts. We don’t mock religion or politics [in our films], it’s just our artistic view of humanity.

“I honestly hope that our audience enjoys our movies for what they are and take from them what they feel like taking. I don’t really mind if they hate our movies. I love it if they love them. I hate it if they are indifferent.”

The Heroines

Fair enough. Now what can we say about women as they are presented in a Pachamama film? Are they captives of their own compulsions, unable to forge their own destinies, as might seem at first glance?

Jac gives us his view, beginning with Ollala.

“Olalla and Ofelia (Olalla’s sister) are not weak because women are not weak. This nonsense of the weaker sex is just that, nonsense. Patriarchy is a response to that strength. At one point men felt the compulsive need to control women first and other men second.”

With a moment’s pause, he adds, “Religion and politics are attempts to control, to make everything fit a pattern that can be controlled. That’s a very primitive view of life.”

It just so happens that when it comes to Church and society, the simpler, the better.

“There’s nothing more scary than women taking over, like in Olalla when she sucks the blood out of her boyfriend. It scares even women, so they have to burn Olalla’s mother,” Jac says.

What about the other films we’ve mentioned?

Jac has his thoughts.

“The female vampires in Dead But Dreaming survive cruel torment, the accused witches overcome their death sentences in Maleficarum.”

“Is Varna [in Dead But Dreaming] taking the route Moira took? Will Justine go on after her ordeal is over?”

Jac states that women in his films are his main focus, and I might add, his source of strength.

“The principal characters in all my movies, including Krik? Krak! are, for some reason, women. They are the heroines in all my stories. Men take second place either as aggressors or victims.

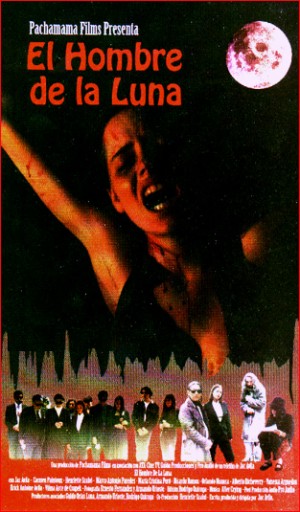

“Even in the miniseries El Hombre de la Luna, where I play the central character, an attorney/painter investigating the death of a young woman, the women in the story solve the problem and rescue the attorney from certain death.”

But Jac’s women do suffer and it seems to have a sexual theme. So how does pain work into the art he and his filming partner Amy Hesketh create?

We’ll look at that next.